AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR THE FORMULATION AND REGISTRATION OF KATHIKAWATH IN RELATION TO NIKAYA OR CHAPTERS OF THERAVADI BHIKKUS IN SRI LANKA; TO PROVIDE FOR EVERY BHIKKU TO ACT IN COMPLIANCE WITH THE PROVISIONS OF THE REGISTERED KATHIKAWATH OF THE NIKAYA OR CHAPTER WHICH RELATES TO SUCH BHIKKU; TO IMPOSE PUNISHMENT ON BHIKKUS WHO ACT IN VIOLATION OF THE PROVISIONS OF ANY REGISTERED KATHIKAWATH, AND FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO.

Author: platform

Up-country Tamils: The Forgotten 4.2%

Sri Lanka has long been synonymous with fine tea; witha plantation history dating back to 1862 to an export value estimated to reach US$ 2,500 million this year, the humble beverage is the island’s pride across the globe. Accounting for nearly 14% of the country’s total export earnings, it is among the nation’s most valuable and prized produce.

This journey to international fame begins in the central hills, ‘Mayarata’, as it was called, the Country of Illusions. Once thickly forested and inaccessible to humans, settlements were limited to open valleys and the city of Kandy. The British cleared these acres of virgin forest and, once their experiment with coffee crops failed, began planting tea; the rest is history.

However, history has and might continue to overlook the most important cogs in the large machine that is the tea industry of Sri Lanka; the people without whose tireless labour this process would grind to a screeching halt – the workers on the tea estates.

Descendants of South Indian labourers first sent here in the 19th and 20th centuries to work in the first British plantations, the ‘up-country Tamils’ or ‘Indian Tamils’ constitute 4.2% of the Sri Lankan population.

Over the years, they have been marginalised by the very country that they devote all their energy to. The Sinhala nationalism that fuelled the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 set such precise terms of identity that even though they had lived on the island for decades, lack of proper documentation meant they were not recognised as citizens of Sri Lanka and left stateless.

A handful of agreements between India and Sri Lanka over next few decades laid out plans to repatriate some while granting citizenship to a select few. Finally, it was the J.R Jayawardene government that came into power in the 1970s that revised the Citizenship Act, adding in a Special Provisions in the form of the Grant of Citizenship to Stateless Persons of Indian Origin, accepting all remaining Indian Tamils as citizens of Sri Lanka, equipping them with a nationality and a vote.

It has been almost 200 years since the first migrant workers made the hill country their home. But is it really a home?

The ‘line’ system that exists in estate housing is the same one established in the late 19th century – a row of small houses, each more similar in size to a single room, that share a roof. These were initially meant to be temporary shelters for the workers yet estate management over the years never sought to develop the living conditions of the workers.

Each family is allocated one of these ‘houses’, meaning everyone lives in uncomfortably close quarters, severely distorting family dynamics. Should a child marry, reproduce and come to live in his/her parents’ house, as it does frequently happen, the situation worsens.

Yet the estate worker is not the owner of his house, even though it is that small. Since the plantation land belongs entirely to the estate, the worker is not provided with a deed or permit that proves that the house is his/hers. Should he plant a tree outside the line, even its fruits would technically belong to the estate management. Because of this system, where the housing comes under the control of the management, individual houses are not provided with an address. This results in administrative issues, problems for the police and issues during voting.

The lack of an address also means important correspondence doesn’t reach the house – all mail must be addressed to the estate’s head office and is distributed at the management’s convenience. Workers don’t receive time-sensitive EPF notices, students who persevere enough to complete their AL education don’t receive their university letters in time and most personal correspondence never reaches the person it was meant for.

Estates, being private lands, do not fall under the Pradeshiya Sabha Act therefore local authorities do not have the power to provide addresses in these areas as the roads too are the estate’s property; their maintenance is the responsibility of the estate.

Tea contributes to a large portion of Sri Lanka’s export revenue yet the infrastructure in place in the tea-growing regions is hardly conducive to the smooth production of the main export of the country. Taking into consideration how important transport is in the tea process, there has been no development of estate roads undertaken by the respective estate management.

This feeds into a range of obstacles in the worker’s daily life. Walking from their line house to the particular area of the plantation they are required to work at, both places sometimes on two different hills, is laborious enough without the badly-maintained road. The walk back after a day’s backbreaking work is hellish.

Classes in estate schools are limited and students who wish to study further have to go into the main town. Hospitals, long since neglected, are not adequate for all emergencies and again, they are forced to resort to services in the town. Access to these are made additionally time-consuming because the roads are so badly damaged and the limited bus services available to estates are irregular.

Youtube link goes here…

Estate schools extend to Grade 5 or Grade 9 in most cases and students who wish to study beyond that resort to making the journey from the estate to the closest city to complete their education. Kids talented in sports or the arts don’t have as many options for progression in their fields as a child in the town would. While most schools would employ teachers who are specialists in their subjects to teach children, some of the young women appointed to estate schools only have an Advanced Level qualifications.

“There’s one bus; if they miss the one bus to school then the children have to walk between the tea bushes, on trails that are so steep and jagged that it’s life threatening. So, most often, they stop going to school. Children start working on the estates early or get married at a young age and have families of their own. Because these conditions are so bad, most government teachers appointed to estate schools don’t even come to teach for so long – they prefer places where they are familiar with the culture and where conditions are not so harsh. These schools are just forgotten.”

Though there are hospitals buildings in the estates, most of them have fallen to disarray after years of neglect and those that do function can only administer treatment for the most basic ailments. Surgeries and delivery of babies has to be done by trained doctors in a town hospital.

“She’s pregnant now and when my wife has to give birth, it will be very difficult for us. I have to take her almost 40 kilometres away to the hospital in the main town at the bottom of the mountain along these roads that are so damaged, the journey will be very uncomfortable for her.”

Health issues are constantly mounting in the cramped living conditions. A single line with five or so houses share a wall and with more than five people living in a single room, contagious diseases spread rapidly. In addition, most estates don’t have a proper toilet system for the inhabitants of the line houses to use. Water distribution in some plantations is such that the same water used by lines higher up the mountain makes its way down a channel to the lower divisions and the individuals there are left having to use water that is far from pure. Even in places where this particular system is not used, irregular water distribution methods and lack of basic hygiene facilities contribute to prevailing health dilemmas.

The options available to women who wish to work outside the estate are very limited. Aspiring to reach greater heights than the generations before them, idealistic women look for jobs in Colombo – working in someone’s house or in a garment factory. Their other option is to look for labour work abroad, which they sometimes find difficult to adjust to because of the culture differences. Eventually, most of them return only to marry and begin their own families and start, inevitably, working on the estate.

Though some do make these journeys, some fall into the cycle of the culture and are married as soon as they come of the legal age. Young brides bear children at a young age and are thereby compelled to stop schooling to take care of and provide for the children.

The consumption of alcohol by men, to beat the cold of shivering temperatures around the mountains and as an antidote to a day’s hard work, has resulted in an increased number of cases of violence against women and children.

This habit has spread among the women too. Because the communities consume illicit alcohol that is not manufactured properly, sickness results.

To approach the relevant authorities that could possibly help address their concerns is also difficult for the workers; even though the communities are Tamil, government agents appointed to offices in these areas are mostly Sinhala and the language barrier creates more confusion. Police stations, hospitals and other entities working directly with the people are not able to communicate using the language of the region’s majority.

This is one of the many factors that contribute to lack of proper documentation in the estate communities. Birth certificates are not issued or don’t carry accurate information, individuals do not have national identity cards and when couples marry, they do not seek to obtain a marriage certificate. Lack of awareness of the administrative procedures due to being cut off from society reinforces these inactions.

Tea country is a maze of bushes set on the face of steep mountains, along trails of jagged ground that drop sharply down the slope. The prevailing chill and freezing cold at some times of the year make for a challenging climate on the best of days.

Manufacturers will justify the use of human labour for the tea-plucking process due to the need for meticulous attention to detail in the quality of the leaves that result in a world-class beverage.

The average wage an estate worker is paid is Rs. 600 for 21 complete days of work.

However, superintendents hold back in giving work, asserting that the leaves are not yet ready for plucking; this means some workers can’t fulfil the quota and thereby have their pay reduced. Estates have taken to hiring workers on a ‘temporary’ basis, where they are paid by the kilogram at a rate that is much lower than the wages of the permanent worker; all far too little considering the harsh working conditions and the denial of any other labourer benefits to the workers.

This is where the youtube link goes…

Over the years, the estate Tamils have been a community marginalised by the state and mistreated by the corporations that employ them. The distance from an estate to the nearest town and the tight working schedules helps the estate management to keep them cornered from and uneducated about society. Unions, who should be advocating worker’s demands for benefits, shy away from their responsibility due to political influence. These workers have not been made aware of the benefits they should be receiving as employees and rights they are able to exercise as citizens of Sri Lanka.

The Centre for Policy Alternatives has worked with local government on gazettes and policies to develop estate roads, provide addresses to these communities and to furnish several individuals with identity cards. Information and anecdotes were gathered during a field study carried out during the months of March and April in estates across the Central and Uva provinces.

Text and photographs by Amalini De Sayrah.

Bring them home: The long search for Sri Lanka’s ‘disappeared’

13 November 2015: The crowd consists primarily of women, but several men are also present. They are young and old, some with children and some needing help to walk. A quick ear to the conversations flying around indicates that they are largely Tamil speaking. In certain areas, there are Muslim women and in others Sinhalese women, though fewer in number. They are all united in their search for missing loved ones.

These women wait for their turn, sometimes for hours, to tell their story before the Presidential Commission to Investigate into Cases of Missing Persons – often referred to as the Commission of Inquiry or COI. Since 2013, the COI has been looking into cases of enforced disappearances during the Sri Lankan civil war. It has been mandated to address cases between 1983 and 2009. The 3-member Commission began hearing complaints in Kilinochchi in January 2014.

“My son was taken from Pesalai in 1989. He was 26 at the time, after his A/Ls he went in search of jobs to Colombo and stayed with my sister-in-law. He sent word through a lorry driver saying he needs 5000 to go abroad but my son didn’t go to claim the money. I heard from relations that Army had taken him in and put him in Magazine prison. I went there, wrote down his name and asked them to show him to me but they said no such person has been brought there. I then went to Bogambara prison; same reply. Welikada prison; same reply. Thalaimannar prison; same reply. I finally reported the incident.”

The response to the call for complaints was overwhelming; thousands of citizens came forward with cases of missing loved ones. Many of the complainants had gone before several state initiatives including previous commissions. With the overwhelming number of complaints made and the need for more time for investigations and inquiries, the Commission’s mandate was extended till August 2014.

Following the extension to the Commission’s mandate, another amendment was made regarding the period they were authorised to investigate – the Gazette provided that they would investigate cases that had occurred between 1st January 1983 and 19th May 2009.

July 2014 saw a further expansion of the Commission’s mandate; ‘to include inquiring into a wide range of issues spanning from violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL) including the recruitment of child soldiers and suicide attacks, to the criminality of financial and other resources obtained by the LTTE.’

CPA initially expressed concerns at this stage when the expanded mandate was presented, stating that it ‘fears for the integrity of the Commission, in particular, that its primary task of investigating and inquiring into the thousands of missing persons in Sri Lanka will be severely curtailed by the present gazette.’ [Read the statement in full.]

‘We were crossing from Mullivaikkal to Vattuvaikkal point. The Army stopped my son. I wanted to take him with me, but the Army said they will inquire and send him back, so we trusted what they said. We were taken in a van and dropped at the camp. Until now my son is missing. My son wasn’t involved in the movement, he came fishing with me. Is is safe with the Army around? I don’t know…..’

At the same time an Advisory Council was appointed to advise the Commission. Issues were raised as to the independence of this Council and questions still remain as to the nature of the work it set out to do and how this work will support that of the Commission.

Concerns were raised by CPA and other members of the civil society on the appointment of Sir Desmond de Silva to this advisory panel, claiming that it ‘further discredited a Commission of Inquiry that has failed to earn the confidence of victims and overburdened it with a mandate that was meant to address the overwhelming cases of missing persons from across Sri Lanka, raising serious questions about the willingness of the government to address the issue of enforced disappearances.’ [Read the statement in full]

Though the mandate of this Council was not made known, their report was made public at the end of October – read it in full here.

“He went missing from the Savanagara area in 1994; 3 others had joined him and they had gone fishing. They were coming down the road when they went missing. Army and terrorists were both moving around the area – I don’t know who to blame. I went to 3 LTTE camps in Mannar looking for him. Those at the LTTE camp during Chandrika’s time told me that there’s a UNP government and that I should go ask them. We were told they are free to move around and to look for him ourselves. We searched first at the Thalaimannar camp and then at the Alayadivembu camp. During our search, we heard that there was a problem between Prabhakaran and Karuna and we were ordered to go home.”

“She was 18 at the time and going to school when she went missing in 2006. It was a very problematic time; she was taken by force on her way home, by the LTTE in June that year. We were also displaced, but I met her in Kilinochchci; she said she was alright and not to worry about her. She was studying computing under the LTTE. She came home once after being taken. We ended up at Pudumatalan refugee camp. My other daughter got

wounded in a shell attack and I went with her to hospital. It was under LTTE control and there was shelling so they shifted us to Mannar hospital for treatment. At Omanthai checkpoint, my eldest daughter had surrendered – the village girls had seen and spoken to her. I want her back. My other wounded daughter was sent to Dambulla hospital, but since it was a military hospital I wasn’t allowed to see her. Maxwell [Paranagama] said he will check with the hospital records but I have heard nothing.”

An interim report by the Commission was submitted to the President in March 2015 but this report was not made public until very recently. Initially, a statement on the report was sent, to the media, stating that responsibility for 60% of the cases in the Northern Province were attributed to the LTTE, 30% to the security forces, 5% to armed groups and 5% to unknown groups.

CPA wrote to the commission in this regard, stating ‘the lack of transparency regarding this report which one hopes sheds light on the progress of the work of the Commission.’ [Read full statement here.]

The sittings after the submission of this report saw the addition of two more commissioners to hear the ever-increasing number of complaints made by affected citizens.

“There are 5 camps in that area. Whoever goes on that road, they must pass this area. As you pass the camps and go through the Sinhala area, there are cut outs, road blocks and a Police station. Maoya junction, we were able to search upto there but not further. Records showed that my son had signed in at one check point and the police are aware of this incident but no one knows what happened after that. My son’s telephone is still functioning.”

Each Commission hearing witnessed hundreds of women coming before sittings, many facing hardships that range from the economic to the physical and emotional. Some make long journeys just to be heard by the Commission and to continue their search for missing loved ones. While many women recount

narratives of missing male family members, there are also men who come before the commission in search of missing female family members. Details available also range from specific names of people in power and camps to where people were taken, to anecdotes such as ‘he was on his way home and he was taken’ or ‘he left for school and never came back.’

An Investigation Team was appointed earlier this year, but its role and functions regarding investigation of cases has not been made known, though Commissioners assure that they have commenced work.

“She was 18 at the time, when the LTTE took her. I saw her at the Vellipuram but that was the last time. I went looking for her when I heard that my child was at the detention camp, my only girl. We couldn’t find her. So far I haven’t gotten any information. I want my child back; I plead with you in all affection, please find my child. No, my housing and livelihood can wait – my search is for my child.’

Further, as the Commission heard about cases across the Northern and Eastern provinces, observers noted errors in the translation.

CPA noted ‘translators’ and the Commission’s lack of contextual knowledge of the affected areas and key issues related to the incidents before the Commission. [Read the report here.]

CPA questioned whether ‘the failure to genuinely address the grievances of over 19,000 complainants a stark reminder of the flaws in and failures of domestic processes that are meant to investigate violations?’ [Read the statement in full here.]

‘My husband was 25 years old at the time. One day, armed Air Force personnel took him away for inquiries – they were in civilian clothing. A Buddhist monk at the China Bay temple helped us – he went and saw that he was being kept in the China Bay Air Force camp. The next time we went there, we were told he had been taken to the Plantain Point Army Camp but when we inquired there, they denied it. I reported it to the ICRC

and the HRC. Later, officers came home to make inquiries and I went to the 4th Floor for this. I faced so many inquiries yet nothing happened. I’m here to request his death certificate and due compensation.’

At present, a death certificate is required to claim compensation. This has resulted in many families not having a choice and having to accept missing loved ones as dead and requesting that the issuing of the death certificate be expedited to ensure they are able to obtain assistance. The economic situation for most families in the North and East is difficult – most work in agriculture and in small shops to make ends meet. Most accept a death certificate purely to receive state social welfare payments that will help them in their daily lives.

CPA proposed a policy recommendation – the issuing of a ‘Certificate of Absence’ to families of the disappeared. This would be ‘an official document issued to family members of the disappeared persons, affirming their status as “missing” as opposed to “deceased.” This option has been used in countries that experienced high numbers of disappearances, based on the perception that it is better tailored to balance family members’ emotional and psychological needs without dismissing the need for active investigation into cases of disappearances.’ [Read full paper here.]

This recommendation was well received and during the recently concluded sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Government of Sri Lanka stated that it would issue this certificate to the families of the missing. Soon thereafter, a cabinet paper proposing the introduction of such certificates was approved by the cabinet based on CPA’s recommendations.

Civil society across Sri Lanka including groups from the North and East have criticized the working methods of the Commission and some have engaged in protests. There have also been several calls to expedite investigations on cases of enforced disappearances.

The government mentioned plans to abolish the Commission, but Chairman Maxwell Paranagama has stated that it will continue investigating cases. This

statement was followed by the release of the Commission’s final report in Mid-October and the news that a round of sittings has been scheduled to take place in Jaffna, mid-November.

The UNHRC resolution, co-sponsored by Sri Lanka, also welcomed the suggestion to establish an ‘Office of Missing Persons’, although its tasks and responsibilities have not been made known to the public.

Consultation with civil society and families of the disappeared, essential to making this a victim-centric mechanism of transitional justice, is key but yet to materialize.

Standing Tall

A study of one organisation’s dedication to fighting violence against women.

Anupama’s* arms are folded, unconsciously protecting herself as she tells her story.

“Since we have two small children, I bore it for some time, thinking he is not a bad person. He will change. Once he is in his senses, maybe he’ll be back to normal.”

That didn’t happen.

It all went downhill after her new husband lost his job while Anupama was still on maternity leave. Her mother in law then began setting her new husband against her. Suddenly, the young family found themselves in the midst of escalating tension, eventually erupting into violence. Initially, Anupama felt powerless.

“I didn’t know anybody here, since I am from a different country, and had the language barrier to face. I didn’t know who to approach,” Anupama said.

In the end, it was her country’s high commission who referred her to Women in Need (WIN) a centre dedicated to eliminating violence

against women, particularly domestic violence.

WIN was trying to mediate a settlement, when suddenly Anupama’s husband filed a court order and took her two young children away

from her. She approached the police, who told her they couldn’t help her without a court order. In the end, Anupama won back temporary custody rights, thanks to WIN’s intervention.

Anupama isn’t alone. Like her, there are many others who are afraid to ask for help. Much of this stems from shame. As Priya* put it, “Often, you are too embarrassed to talk about domestic issues [to outsiders].”

Priya’s son was still in nursery school when her husband turned abusive – and witnessed much of it. Priya’s husband was initially a pavement vendor, but lost his job when the pavement was demolished to make way for a new shop. He then found work at a small ‘hotel’ and began an affair with a much older woman – right in front of Priya and her young son.

Priya too had to fight for custody of her son. What’s more, her husband wasn’t just violent towards his family; he had also killed a boarder who had been staying with him. “I was shattered when I first came here. I had no money, and was living with my mother, who was supporting me. Every morning when I woke up… I couldn’t think of the future. I thought we would die,” she said, recalling those dark days.

Today, Priya has a job at Women in Need, and is able to support herself – she even paid her son’s nursery school fees by herself.

“I’m not afraid any more. Now I can survive on my own,” she says, proudly.

Priya says part of the reason she is able to get up in the morning is her counsellor, who is ‘like a second mother.’

Accessibility view

Chief Counsellor Padma Kahaduwa has been working at WIN for 25 years. She initially joined as a volunteer, but once she received her diploma in Psychiatric Counselling, she joined as a permanent staff member.

Padma’s job never ends. After hours, calls to WIN’s hotline are often redirected to counsellors’ mobile phones. It is the counsellor who is the first point of contact at WIN, talking to the patient and assessing whether they need legal help.

At times, suspicious husbands even call up the WIN hotline, demanding to know why there were missed calls to them. “We had one such call just yesterday, from a man who’s an unemployed drug addict. The wife wants to leave him, but she has two young children. The court has given her a three month period to see if they can settle their differences – but they can’t be settled. Every evening, he takes drugs. He won’t leave her alone,” Padma said.

WIN’s first priority is to try and settle the dispute between an arguing couple. “We talk to both parties to try and negotiate a settlement. If it becomes clear that one can’t be reached, it’s only then that we resort to legal measures,” Padma said. This is to try and disrupt the family as little as possible, since removal of the breadwinner of the house can cause numerous social and financial issues, which can affect young children, Padma explains.

Apart from this, counsellors conduct many activities, from sewing circles to support groups. The groups have been particularly powerful for those recovering from domestic violence, since they can see others in their situation supporting themselves successfully, Padma says. In addition, the group members often meet and support each other even outside therapy sessions.

The Legislation Regulating Domestic Violence

Each year, WIN’s legal department files an average of 15 to 20 domestic violence cases. Currently, there are 25 ongoing. According to the Women and Children’s Bureau, 499 domestic violence cases were filed with the police in 2013 alone. Most people think that the court system in Sri Lanka is fundamentally flawed, with cases dragging on for years.

This isn’t actually true for domestic violence cases, however, which fall under the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act. Most of the women who call the hotline are married and between the age of 20 and 50 years. There are far more calls now than in the past, but the stigma of talking to a stranger about personal issues at home is still strong.

Once it is decided that legal action needs to be taken, a legal officer will attempt to get a protection order from the abusive husband. Usually, an attempt is made to bring the protection order ex parte, i.e. without the husband’s presence. Though not guaranteed, this is usually granted. After this, the husband has to appear before the courts within a period of 2 weeks. Next, a decision needs to be made whether the interim protection order be made permanent. Unlike other cases, domestic violence cases are processed relatively fast thanks to this law. However, this only applies to victims of domestic violence – i.e. wives, ex-wives and co-habitees. What’s more, there needs to be proof of abuse – ideally hospital and police reports. Showing evidence of mental and emotional trauma is also possible under the Act but there are practical difficulties, since a judge has to be satisfied that there is a definite threat.

While domestic violence cases are processed relatively quickly, the emphasis is still on attempting to maintain the family unit. Often, the courts will suggest a short period at home in order to ascertain whether the conflict between a couple can’t be resolved. This results in many victims of violence, like Kumari* going back to their abusive husbands while the court cases are ongoing.

“I was just 19 when I eloped. He told me he was a Sales Executive at Suntel. It was only after I married him that I found out he was a drug dealer,” she said.

When Kumari was admitted to hospital to deliver her first child, the doctor noticed she showed signs of sustained sexual abuse. The ward nurse, a family friend, alerted Kumari’s father, who took her in. Kumari made several police entries, to little effect. She then went to court, and returned home for a 6-month period to try and reconcile with her husband, for the sake of her child, on court orders. She was soon pregnant again.

The doctor who delivered her second child was less sympathetic. In fact, he told other nurses and patients on the ward that Kumari was promiscuous.

“Now I can’t leave the house… I can’t take my children to Montessori. It’s really affected me,” she said, breaking down. “Only the first doctor who spoke to me knows the truth.”

Kumari’s case is still ongoing. She has also been given a job at WIN and is grateful for the support she has received. “My father was supporting me, but I can’t always depend on him.”

One striking similarity between all the women interviewed for this piece was that every one of them asked not to be photographed. They feared that their children would somehow suffer repercussions after they shared their stories.

Apart from their reluctance to be photographed, most of the women interviewed had another thing in common – their reaction upon being asked what they would say to other women in their position.

“Speak up. Don’t stay silent,” Anupama said. “Initially I thought, if the person who I came to this country for, the person I gave my life to, doesn’t understand me, then how can anyone understand me? That was wrong. There are people who understand and care. WIN is one such organisation who gives you confidence and everything is done in a human way.”

“Don’t hide your problems. If you do, you will suffer [in the end]” Priya said. “I have no words to thank WIN for all they have done for me. It is thanks to them that my son and I are alive today.”

WIN’s Services

WIN offers many services apart from counselling and legal assistance.

Crucially, they operate a 24-hour hotline (0114 718585) where women can call in to report incidents of violence. They also offer counselling, legal services, and temporary shelters in Colombo and Matara, providing safe spaces to victims of violence. Going the extra mile, they also have a dedicated desk in several key police stations in Colombo (at the Kirulapona Police Station, Women and Children’s Bureau at the Police Headquarters as well as the Kandy and Weligama Police Stations). Recognising that many abused women do not want to reveal the true source of their injuries, WIN also operates 8 one-stop crisis centres offering counselling in hospitals across the island. 8 more women’s resource centres offer not just a safe space but also library facilities, skills development and outreach programmes for women in Anuradhapura and Matara. In addition, WIN’s successful recycled paper greeting card project gives women recovering from domestic violence the means with which to support themselves.

WIN also provides psychological counselling services, legal advice, awareness programmes, skills development trainings and court representation to female inmates at the Welikada, Kalutara, Anuradhapura, Badulla, Kandy, Jaffna and Tangalle prisons.

*Names changed to protect privacy

Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act No 04 of 2005

AN ACT TO AMEND THE CIVIL PROCEDURE CODE

Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act No 9 of 1991

AN ACT TO AMEND THE CIVIL PROCEDURE CODE (AMENDMENT) ACT, NO. 79 OF 1988

Civil Procedure Code (Amendment Act No 14 of 1993

AN ACT TO AMEND THE CIVIL PROCEDURE CODE

Official Languages Commission Act No 18 of 1991

AN ACT TO ESTABLISH THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGES COMMISSION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC 06 SRI LANKA ; AND TO MAKE PROVISION FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Housing (Special Provisions) Act No 18 of 1974

A LAW TO PROHIBIT THE UNAUTHORIZED TRANSFER OF OCCUPANCY OF PREMISES PROVIDED BY THE COMMISSIONER OF NATIONAL HOUSING OR A LOCAL AUTHORITY OR THE COMMISSIONER OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT OR A PUBLIC CORPORATION FOR OCCUPATION BY ANY PERSON, AND FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Houses of Detention Ordinance No 05 of 1907

AN ORDINANCE TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF HOUSES OF DETENTION FOR VAGRANTS

Cultural Property Act No 73 of 1988

AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR THE CONTROL OF THE EXPORT OF CULTURAL PROPERTY TO PROVIDE FOR A SCHEME OF LICENSING TO DEAL IN CULTURAL PROPERTY ; AND TO PROVIDE FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Agrarian Services (Amendment) Act No 4 of 1991

AN ACT TO AMEND THE AGRARIAN SERVICES ACT, NO, 58 OF 1979

Agrarian Development Act. No. 46 of 2000

AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR, MATTERS RELATING TO LANDLORDS AND TENANT CULTIVATORS OF PADDY LANDS, FOR THE UTILIZATION OF AGRICULTURAL LANDS IN ACCORDANCE WITH AGRICULTURAL POLICIES ; FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT COUNCILS, TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A LAND BANK ; TO PROVIDE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AGRARIAN TRIBUNALS, TO PROVIDE FOR THE REPEAL OF THE AGRARIAN SERVICES ACT, NO. 58 OF 1979 ; AND FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWith or INCIDENTAL THERETO

Agrarian Development Act (Amendment) Act No 46 of 2011

AN ACT TO AMEND THE AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT ACT, NO. 46 OF 2000

Convention of the suppression of Terrorist Financing ACt No 03 of 2013

AN ACT TO AMEND THE CONVENTION ON THE SUPPRESSION OF TERRORIST FINANCING ACT, NO. 25 OF 2005

Convention of the suppression of Terrorism Financing (Amendment) Act No 41 of 2011

AN ACT TO AMEND THE CONVENTION ON THE SUPPRESSION OF TERRORIST FINANCING ACT, NO. 25 OF 2005

Convention Against Doping in Sport Act No 33 of 2013

AN ACT TO GIVE EFFECT TO THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION AGAINST DOPING IN SPORT ; TO MAKE PROVISION FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION IN SRI LANKA OF THE SAID CONVENTION BY THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SRI LANKA ANTI DOPING AGENCY AND FOR SPECIFYING THE APPLICABLE DOMESTIC LEGAL MECHANISM TO COMBAT DOPING IN SPORT WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE AFORESAID CONVENTION ; AND TO PROVIDE FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

National Human Resources Development Council of Sri Lanka Act No 18 of 1997

AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL OF SRI LANKA, FOR THE PURPOSE OF INITIATING, PROMOTING, AND PARTICIPATING IN THE IMPLIMENTATION OF, POLICIES RELATING TO HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT ; AND FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR 1NCIDENTIAL THERE TO

International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights (ICCPR) Act No 56 of 2007

AN ACT TO GIVE EFFECT TO CERTAIN ARTICLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS (ICCPR) RELATING TO HUMAN RIGHTS WHICH HAVE NOT BEEN GIVEN RECOGNITION THROUGH LEGISLATIVE MEASURES AND TO PROVIDE FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka Act No 21 of 1996

AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA ; TO SET OUT THE POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF SUCH COMMISSION ; AND TO PROVlDE FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Age of Majority Ordinance No 7 of 1865

AN ORDINANCE TO MAKE THE AGE OF EIGHTEEN YEARS THE LEGAL AGE OF MAJORITY IN SRI LANKA

Age of Majority (Amendment) Act No 17 of 1989

AN ACT TO AMEND THE ACE OF MAJORITY ORDINANCE

Adoption of Children Ordinance No 24 of 1941

AN ORDINANCE TO PROVIDE FOR THE ADOPTION OF CHILDREN, FOR THE REGISTRATION AS CUSTODIANS OF PERSONS HAVING THE CARE, CUSTODY OR CONTROL, OF CHILDREN OF WHOM THEY ARE NOT THE NATURAL PARENTS, AND FOR MATTERS CONNECTED WITH THE MATTERS AFORESAID

Animals (Amendment) Act No 46 of 1988

AN ACT TO AMEND THE ANIMALS ACT, NO. 29 OF 1958

Animals (Amendment) Act No 10 of 2009

AN ACT TO AMEND THE ANIMALS ACT, NO. 29 OF 1958

Animal Feed Act No 15 of 1986

AN ACT TO REGULATE, SUPERVISE AND CONTROL THE MANUFACTURE SALE AND DISTRIBUTION OF ANIMAL FEED AND TO PROVIDE FOR MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH OR INCIDENTAL THERETO

Brothels Ordinance No 5 of 1889

AN ORDINANCE TO PROVIDE FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF BROTHELS

Bribery Act No 11 of 1954

AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF BRIBERY AND TO MAKE CONSEQUENTIAL PROVISIONS RELATING TO THE OPERATION OF OTHER WRITTEN LAW

Bribery (Amendment) Act No 20 of 1994

AN ACT TO AMEND THE BRIBERY ACT

Powers of Commissioner in regard to industrial disputes. [ 2, 35 of 1956]

(1) Where the Commissioner is satisfied that an industrial dispute exists in any industry or where he apprehends an industrial dispute in any industry, he may- (a) if arrangements for the settlement of disputes in that industry have been made in pursuance of any agreement between organizations representative respectively of employers and workmen engaged in that industry, cause the industrial dispute to be referred for settlement by means of such arrangements, or (b) endeavour to settle the industrial dispute by conciliation, or (c) refer the industrial dispute to an, authorized officer for settlement by conciliation, or [ 2, 62 of 1957] [ [3,4 of 1952] (d) if the parties to the industrial dispute or their representatives consent, refer that dispute, by an order in writing, for settlement by arbitration to an arbitrator nominated jointly by such parties or representatives, or in the absence of such nomination, to an arbitrator or body of arbitrators appointed by the Commissioner or to a labour tribunal. [ 3,4 of 1962] (2) A body of arbitrators appointed under para- graph (d) of subsection (1) shall consist of- (a) a person nominated by the employers, (b) a person nominated by the workmen, and (c) a person nominated as Chairman jointly by the employers and workmen, or, in the absence of such nomination, by the Commissioner. The opinion on any matter of the majority of the members of a body of arbitrators shall be deemed to be the opinion of that body on that matter. (3) Where an industrial dispute is not settled in consequence of action taken by the Commissioner under any of the paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and (d) of subsection (1), he may, if he considers it expedient to do so, take action, as often as he considers it necessary so to do, in respect of that dispute under any of those paragraphs.

Functions of Commissioner in regard to industrial disputes.

(1) Where, upon notice given to him or otherwise, the Commissioner is satisfied that any industrial dispute exists or is apprehended, it shall be the function of the Commissioner to make such inquiries into the matters in dispute, and to take such other steps, as he may think necessary with a view to promoting a settlement of the dispute, whether by means referred to in this Act or otherwise. [2,4 of 1962]

(2) For the purposes of this section, “Commissioner” includes a labour officer

Short title

This Act may be cited as the Industrial Disputes Act

Wee

79790yo

Title 3

This is a testing title 2

dsfsd

This is a testing title

Section 1.10.32 Of “De Finibus Bonorum Et Malorum”, Written By Cicero In 45 BC

“Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?”

Short Title and commencement

(1) This Act may be cited as the Companies Act 1993.

(2) This Act shall come into force on 1 July 1994.

Administration and Daily Life

Numerous cases exist among Government officials including Grama Niladharis not knowing the language spoken by the people of their own division, resulting in the lack of an official whom one can address in one’s own language, when visiting government department.

Routine procedures from lodging a complaint at a police station, seeking health care at a govt. hospital, applying for compensation or pensions, obtaining licenses, registering a birth, death or marriage, or traveling are made experiences of anxiety for any Sri Lankan who does not know Sinhala.

Access to Information

Signage- Though accepted that all government institutions, particularly in bilingual areas, should have all sign boards, street name boards and official documentation in all three languages, the ground reality is that a number of government institutions do not display such nameboards or provide official documents in all three languages. For example in the Colombo district DS divisions such as Thimbirigasyaya and Kotahena are not implementing this policy to any extent recognizable resulting in sections of the minority communities receiving some of their most essential documents such as birth, death and marriage certificates in a language not their own.

Product Information- Pharmaceutical industry violations:

Another area of serious violations of language rights in practice, is within the pharmaceutical industry, where almost all drugs, equipment and medications are currently labeled only in English. Sinhala and Tamil consumers, who make up the majority in this country, when they purchases drugs have no idea of the quantities, dosages, side effects, alternative brands or other relevant information important to patients and caregivers. This adds to the inconvenience in government hospitals in the North and East in particular where some doctors, nurses and other medical staff too do not speak Tamil. So for a person who is already insecure, in pain and fear due to illness or injury, having to deal with ineligible information about medications is further misery.

Access to Education

Sri Lanka’s public education system has included teaching in both Sinhala and Tamil even since colonial times. However In practice many areas have no schoolteachers in the relevant language. Letters issued by zonal education offices are in Sinhala alone. Tamil teachers have been sent Teaching Guides in Sinhala. Translations are sent very late, often too late to be of any use. In schools in bilingual areas such as Colombo, student assemblies are held only in Sinhala. School children often have no access to official translations, and any communications from their school are sent to the parents in Sinhala. Sometimes the parents cannot even enter school premises because they do not speak Sinhala. Universities host certain courses only in English and Sinhala thus violating minority rights to equal access to education.

Access to Justice

At any stage of the judicial process, where an accused is unable to defend him/herself in his/her mother tongue and is forced to rely on inaccurate translations, a serious miscarriage of justice arises. As found from interviews, among other issues, complaints made by Tamil citizens are recorded in Sinhala at Police Stations, and the complainants are subsequently asked to sign these statements(Vavunia, Trincomalee, Mannar and Ampara), Tamil citizens in the Eastern Province receive summons in Sinhala, and court transactions and case hearings in many areas of Sri Lanka are conducted in only Sinhala.

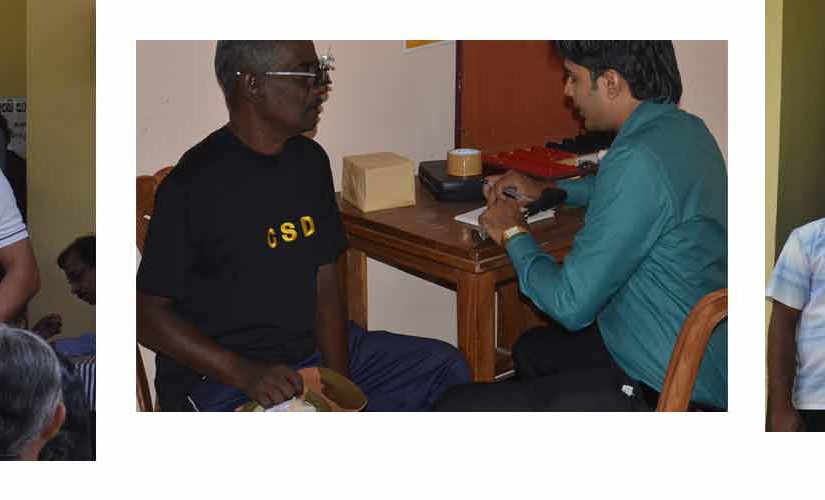

HEALTH CAMP FOR JAYANTHIPURA CITIZENS

As part of the work of Citizen Councils in Kantalai it has been identified that the issue of Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Origin(CKDU) is taking a sizeable toll on the citizens of Jayathipura, Kantalai. More than 50 persons have died in that area alone in the last two years from CKDU.

The Jayanthipura Citizen Council working with a partner organisation of the Centre for Policy Alternatives, the National Collaboration Development Foundation, Kantalai recently organised a One Day Health Clinic to meet families of the affected and citizens of the area to discuss the issue, and the strategy for tackling this, with the kind participation of a number of medical experts.

Held on 11th September 2015 at Jayanthipura Community Health Centre, Jayanthipura, the clinic provided services for testing of blood and urine, blood pressure and also hosted an eye-camp for donation of reading glasses to needy citizens. A number of doctors, MOH and hospital staff, media personnel and citizen council members participated, including representatives from military authorities who supported the free services clinic.

Key volunteer participants included MOH personnel, Dr Costa and Dr Shermila and Dr Bandara Seniviratne from Aranaganwilla, Mr. Terrence Gamini, Head of the Anuradhapura Protection Foundation, optician Dr Charith, and Kidney Disease expert Dr Rajiv Dissanayake (Anuradhapura KPF). Ven Prof Pallegama Sirinivasa Himi, Chief Incumbent of the Jayanthipura Viharaya and Brigadier Kamal Pinnawala of the 222 Jayanthigama Brigade extended their blessing and support to the camp and Chairperson Ajith, and Jayatissa of the Jayanthipura Citizen Council, are among the many who contributed to the success of the clinic. The Lions Club of 306 donated 100 sets of eyeglasses and an OPD clinic was held for almost 200 citizens of the area.

The Jayanthipura Citizen Council kindly offered midday snacks for all participants and CPA helped to facilitate the event.

.

ADDRESSING CIVIL RIGHTS IN THE ESTATE SECTOR

Their hard labour powers the multimillion dollar industry that is Sri Lankan tea. But the estate sector workers including those of the Badulla district are still some of the poorest, most marginalised people in Sri Lanka. Fostered by a system that does not want to let go its hold on cheap labour, conditions in the estate sector of the Uva Province have remained almost unchanged by recent post war development drives. Exemplifying the administrative neglect of these communities is the fact that many plantation sector workers have never had a permanent contact address to their name.

Meet Kamala*. Her entire lifetime of EPF savings in a cheque, was enchased by another woman of the same name, in the same estate who got hold of it, because her mail had been delivered to the wrong address. Her thoughtful countenance, while she is listening to the other sad stories her neighbors tell, is one of deep disillusionment.

Who knows what would have happened to a very studious young man named Kumar. if he had only received the letter that told him that he had in fact been selected for university admission? After studying very hard, amidst great odds, a chance of a lifetime, a way out of a life of deprivation and hardship, was missed because of a letter misdirected. He is now a teacher in a remote village, living a mundane difficult life, unheard of and hopeless. Simply because one letter was lost.

Many line rooms in the plantation sector are not numbered and letters are often delivered to other people with the same name. Whether a person receives a letter depends on the integrity of thekankami(official who organizes distribution of these) the good will of ones neighbours , often sorely lacking, and sometimes, sheer chance…

Safeguarding the civil rights of plantation sector workers

Funded by the Australian High Commission, SL, the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) along with a local partner Uva Shakthi Foundation, has worked on a pilot project in Passara ,Badulla(Uva Province) aimed at bringing a modicum of dignity into the lives of this marginalized community whose human rights have been routinely denied. In the last six months this project has arranged to provide permanent addresses, for the first time ever in the plantation sector, for no less than 3000 families of estate workers. The project also organized setting up secure mail collection boxes in20 localities, selecting road names and providing signage for 40 of the estate by-roads in the area, in an endeavor to safeguard the delivery of correspondence.

The lack of National Identity cards among some workers, another problem addressed by the project, leads to a number of serious issues, eg. limited freedom of movement, difficulty in making transactions, vulnerability in civil and criminal cases, lack of security, complications in obtaining official documentation and finding employment etc

Mobile clinics were hosted to speed up the application process formore than 300 National Identity Cards, which may otherwise reach owners late or never. The latter is particularly relevant to a large number of students who were due to sit for exams shortly.

The right to safely receive one’s correspondence, taken for granted in the rest of the country but fraught with difficulty in this area, can make the difference between receiving a rare university admission, a job in Colombo, a desperately needed remittance from a relative abroad…or not. In the lives of estate worker communities such rare opportunities may come only once or twice in a lifetime and be the difference between hope and a life of regrets

This project has been graciously sponsored by the Australian High Commission, SL

*not their real names.

WHO BROUGHT ABOUT THE TRILINGUAL NIC ?

The Sinhala Tamil National Identity card -Whose victory is this?

The Island Newspaper of 1st March 2014 published an article in the front page, with a photograph saying that a newly printed Sinhala and Tamil, Bilingual National Identity card including personal details was introduced by the Department for the Registration of Persons on the 28th February 2014.

Other than the Island newspaper many other newspapers had published this news with some prominence. Some newspapers had shown an interest in this previously too. For example during the 1stweek of February the Lakbima newspaper had published a report, with a photograph, that work was in progress those days in the experimental stage of producing a new National Identity Card.

All these newspaper reports publicized an idea that the introduction of the new National Identity Card was due to a requirement by the Department of Registration of Persons. This is how the Lakbima newspaper had reported this fact : “In order to prevent the problems that are incurred with the present National Identity Card work had commenced rapidly these days in the Department of Registrations of Persons to issue an new identity card using modern technology according to the idea of the commissioner General Mr. R.M.S Sarath Kumara. “

The Divaina newspaper reported the following about this on 1st of March.

“The newly printed Sinhala and Tamil bilingual National Identity Card including personal details had been introduced yesterday (28thFebruary) by the Department of Registrations of Persons.”

These newspaper reports indicate that the issuing of the new identity card was initiated due to the requirement of the Commissioner General of the Department of Registrations of Persons Mr. R.M.S Sarath Kumara. None of the reports that were published in the media stated that there had been any other citizen’s actions behind this. Therefore it is natural that the ordinary citizens of this country come to this conclusion. This is because they get news from reports that are published by the media. Yet, is it the truth? What actually happened? It is the right of the citizens of this country to know the correct information. By knowing this, the citizen gets an opportunity to realize the strength of the citizens actions in this country.

The need for an Identity Card including bilingual personal details, has been prevalent for a long time in this country. This is because when the Sinhala language and the Tamil language are the Official Languages of a country, it is a violation of the language rights of that country, when the primary letter that a citizen possess, being the National Identity Card is issued in a single language.

Due to this reason, although the citizens of this country, who had been persevering about language rights had published various ideas, there had been no decisive citizen action taking place about it.

In the y ear 2013, an Advanced Level student took part in a decisive intervention. That student is Anuradha Prasad Dananajaya Guruge from Maharagama who is an advanced level student in Ananda Vidyala Colombo. This student submitted a petition to the Supreme Court asking for the National Identity Card to be issued in both the Sinhala and Tamil languages.

Anuradha Prasad Dhananajaya Guruge, submitting his petition, to a three member bench including Chief Justice, Mr Mohan Pieris, stated that, because the National Identity Card is issued in Sinhala only, immense difficulties are faced by him, when he travels to the Northern and Eastern Provinces, on official business , where administrative work is done only in the Tamil language.

When this petition was heard again on the 21st October last year, the Supreme Court issued an order to the Department of Registration of Persons to issue all National Identity Cards in both languages, from the 1st of January 2014.

Furthermore according to orders issued by the Supreme Court regarding this petition ( STFR 93 of 2013) the Department of Registration of Persons should take steps to issue National Identity Cards in all three languages within the next three years.

Yet the Commissioner General of the Department of Registration of Persons had been unable to fulfill the prescribed order. Although this order had stipulated that the bilingual National Identity Card should be issued from 01st January 2014, the Vibhasha Newsletter on investigation found out that those arrangements had not been completed by the month of February.

Clearly it meant that the order from the Supreme Court had been disobeyed. In any case, the fact that the Commissioner General had made a great effort to publicize himself as victorious in issuing such National Identity Card even two months later than the stipulated date was evident from the news reports that were published later.

The Commissioner General should honestly think about how ethical this (publicity) is. On the other hand, the manner in which the media acted in the matter is also clearly problematic. The issuing of Sinhala Tamil bilingual National Identity Card is a victory for the citizens of this country.

Yet, when reporting this victory by not reporting correctly the true story behind it, many media of this country had avoided their responsibilities. It is a clear that the English media, as well as the Sinhala media had reported about this, without researching facts properly.

This may not have been a wrong that was pre-planned. Yet when incomplete reporting has been done, knowingly or unknowingly it is the reader who has to suffer the bad consequences.

When observing this situation, the most important part of this story has been deleted from the reporting. The fact that knowledgeable citizens intervened and their rights were obtained by the action of citizens, are facts that were thus missing.

In particular, the fact that a national policy had been changed by the intervening of a school student shows a milestone in the history of this country.

It is natural for the reader to have a new enthusiasm for his/her rights after reading this news. Such reporting would encourage the ordinary citizen to stand up for his / her rights. This is why it is a social duty of the media to report such news correctly.

Gaveshi- (Excerpt from Vibhasha Magazine )

See anything wrong with this photo?

Language and Culture

We believe that in order to understand each other and to live in harmony with other cultures and religions, we must first respect people’s mother tongue.

Read about the official language policy of Sri Lanka and make a PLEDGE to respect language rights.

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”

-Nelson Mandela

The Language and Culture Subcommittee aims

- To protect Language Rights, recognising that they are fundamental to the safeguarding of human rights

- To promote a trend against discrimination due to caste difference, status, religion and ethnicity etc

- To launch religious, inter-religious exchange programmes and discussions that focus on the core values of religions.

- To protect ancient artistic traditions and traditional artisans

- To initiate a discussion on literature, visual art, and folk art, to promote appreciation.

- To take steps to initiate a mini library of writings, books and papers, literature, cinema and Teledrama DVDs etc that are useful for the active Citizen Council.

Youth Affairs

Youth are the leaders of tomorrow. They need to be informed, guided and shaped so that they reach their maximum potential. The youth of Sri Lanka in particular have suffered much due to revolution and intolerance, and yet it is within their hands that lie the greatest potential for understanding, reconciliation and advancement.

Youth SubCommittees aim

- To promote respect for language rights among youth

- To encourage youth in critical & analytical thinking

- To use creative input of youth in development

- To get input from youth in planning and decision making

- To give youth opportunities for skills development and chances to demonstrate their creativity

- To promote youth participation in governance

Women and Children

All around the civilised world, gender equality is at the heart of the move towards better society. Children are the citizens of the future, they should be cherished protected and guided. See what the citizen’s councils are doing to empower women and to safeguard children.

“Our children have a right to equal opportunities, to strive, to be happy, and healthy and safe”

-Shakira at the UN General Assembly 2015

The role of the Women’s and Children’s SubCommittee is

- To ensure that children have a safe & happy childhood

- To involve women and children in social development activities of the village

- To protect the rights of women and children

- To encourage and promote handicrafts/cottage industries/arts by women and children.

- To organize free nutrition, physical and mental health clinics and access to legal advice for women, people with special needs, and children

Environment

Citizens need to understand the geopolitical forces that affect their environment and be able to monitor and hold their governments accountable in this regard. Environmental justice needs to be upheld as integral to human rights.

“When the last tree is cut and the last fish killed, the last river poisoned, then you will see that you can’t eat money.”

― Chief Seattle

Environment subcommittees aim

- To spread awareness of the sustainability of progress in agriculture, dairy and fisheries projects

- To give attention to appropriate agricultural methods

- To promote organic farming, reducing harmful side effects in agricultural production and identifying alternatives

- To conserve and promote indigenous medicinal plants, endemic seeds,& biodiversity.

- To host programmes protecting the environment, alerting on mining, sand mining, garbage disposal, burning/felling of forests.

- Monitor and ensure environmental justice in the village

Good Governance

Citizens need to engage with governments to ensure that their rights are protected and their aspirations reached.

The role of the Good Governance SubCommittees of Citizen Councils are as follows:

- To provide information about the role of institutions serving the people eg The Police, DS, Family Health Service, Grama Niladhari, Agrarian Officer, Samurdhi Development Officer, Estate Superintendent, Fisheries Society, Women’s organizations, Funeral Assistance Societies, Three- wheelers Associations, Religious organizations, Public Health inspectors, LG institutions, Provincial Councils and Central Government.

- To educate the citizen on his/her right to question these institutions

- To initiate a discussion on the various improvements that can be made in the service provision of these and initiate necessary

- ADDRESSING CIVIL RIGHTS IN THE ESTATE SECTOR

- HEALTH CAMP FOR JAYANTHIPURA CITIZENS

- CPA’s Outreach and Capacity Building team helps provide addresses for 1,500 plantation sector families in Maskeliya ( Daily FT Saturday, 12 March 2016)

- Photo gallery of The Distribution of Address to the Mocha estate in Maskeliya

Essential requirements

The standard Lorem Ipsum passage, used since the 1500s

“Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.”

Section 1.10.32 of “de Finibus Bonorum et Malorum”, written by Cicero in 45 BC

“Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?”

Meaning of solvency test

The standard Lorem Ipsum passage, used since the 1500s

“Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.”

Section 1.10.32 of “de Finibus Bonorum et Malorum”, written by Cicero in 45 BC

“Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?”

Public notice

The standard Lorem Ipsum passage, used since the 1500s

“Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.”

Section 1.10.32 of “de Finibus Bonorum et Malorum”, written by Cicero in 45 BC

“Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?”

Interpretation

The standard Lorem Ipsum passage, used since the 1500s

“Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.”

Section 1.10.32 of “de Finibus Bonorum et Malorum”, written by Cicero in 45 BC

“Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?”

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!